COMPOSITION

-

9 Best Hacks to Make a Cinematic Video with Any Camera

Read more: 9 Best Hacks to Make a Cinematic Video with Any Camerahttps://www.flexclip.com/learn/cinematic-video.html

- Frame Your Shots to Create Depth

- Create Shallow Depth of Field

- Avoid Shaky Footage and Use Flexible Camera Movements

- Properly Use Slow Motion

- Use Cinematic Lighting Techniques

- Apply Color Grading

- Use Cinematic Music and SFX

- Add Cinematic Fonts and Text Effects

- Create the Cinematic Bar at the Top and the Bottom

DESIGN

-

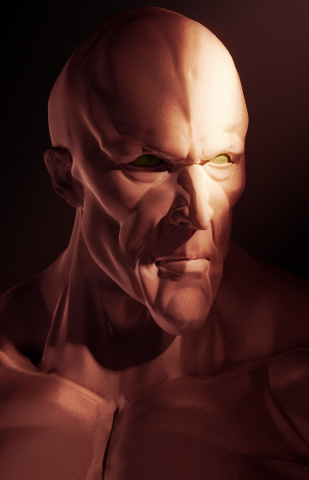

Mike Mitchell x Marvel x Mondo – Iconic portraits of Marvel’s huge stable of heroes and villains

Read more: Mike Mitchell x Marvel x Mondo – Iconic portraits of Marvel’s huge stable of heroes and villainshttps://mondoshop.com/blogs/gallery/16910155-mike-mitchell-x-marvel-x-mondo

https://time.com/69659/marvel-comics-mike-mitchell-artist-portraits/

COLOR

-

Scene Referred vs Display Referred color workflows

Read more: Scene Referred vs Display Referred color workflowsDisplay Referred it is tied to the target hardware, as such it bakes color requirements into every type of media output request.

Scene Referred uses a common unified wide gamut and targeting audience through CDL and DI libraries instead.

So that color information stays untouched and only “transformed” as/when needed.Sources:

– Victor Perez – Color Management Fundamentals & ACES Workflows in Nuke

– https://z-fx.nl/ColorspACES.pdf

– Wicus

-

3D Lighting Tutorial by Amaan Kram

Read more: 3D Lighting Tutorial by Amaan Kramhttp://www.amaanakram.com/lightingT/part1.htm

The goals of lighting in 3D computer graphics are more or less the same as those of real world lighting.

Lighting serves a basic function of bringing out, or pushing back the shapes of objects visible from the camera’s view.

It gives a two-dimensional image on the monitor an illusion of the third dimension-depth.But it does not just stop there. It gives an image its personality, its character. A scene lit in different ways can give a feeling of happiness, of sorrow, of fear etc., and it can do so in dramatic or subtle ways. Along with personality and character, lighting fills a scene with emotion that is directly transmitted to the viewer.

Trying to simulate a real environment in an artificial one can be a daunting task. But even if you make your 3D rendering look absolutely photo-realistic, it doesn’t guarantee that the image carries enough emotion to elicit a “wow” from the people viewing it.

Making 3D renderings photo-realistic can be hard. Putting deep emotions in them can be even harder. However, if you plan out your lighting strategy for the mood and emotion that you want your rendering to express, you make the process easier for yourself.

Each light source can be broken down in to 4 distinct components and analyzed accordingly.

· Intensity

· Direction

· Color

· SizeThe overall thrust of this writing is to produce photo-realistic images by applying good lighting techniques.

-

Gamma correction

Read more: Gamma correction

http://www.normankoren.com/makingfineprints1A.html#Gammabox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamma_correction

http://www.photoscientia.co.uk/Gamma.htm

https://www.w3.org/Graphics/Color/sRGB.html

http://www.eizoglobal.com/library/basics/lcd_display_gamma/index.html

https://forum.reallusion.com/PrintTopic308094.aspx

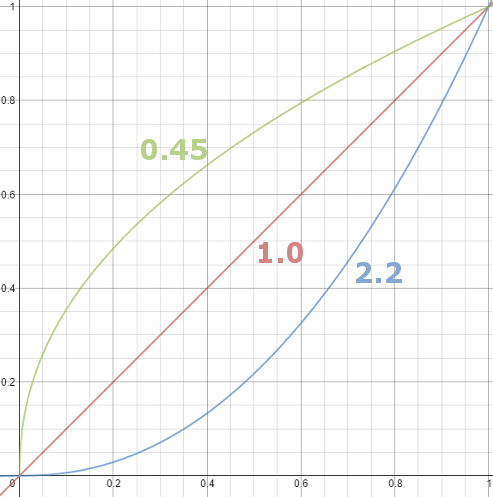

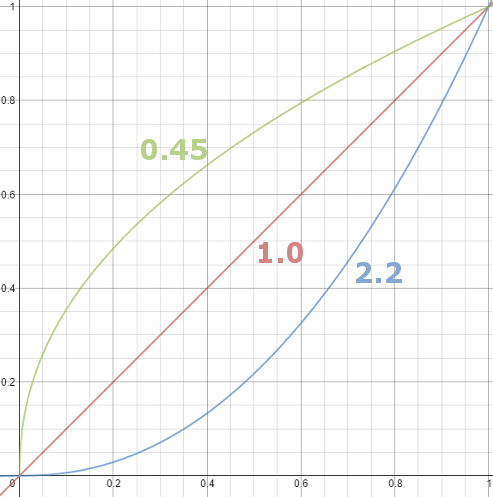

Basically, gamma is the relationship between the brightness of a pixel as it appears on the screen, and the numerical value of that pixel. Generally Gamma is just about defining relationships.

Three main types:

– Image Gamma encoded in images

– Display Gammas encoded in hardware and/or viewing time

– System or Viewing Gamma which is the net effect of all gammas when you look back at a final image. In theory this should flatten back to 1.0 gamma.Our eyes, different camera or video recorder devices do not correctly capture luminance. (they are not linear)

Different display devices (monitor, phone screen, TV) do not display luminance correctly neither. So, one needs to correct them, therefore the gamma correction function.The human perception of brightness, under common illumination conditions (not pitch black nor blindingly bright), follows an approximate power function (note: no relation to the gamma function), with greater sensitivity to relative differences between darker tones than between lighter ones, consistent with the Stevens’ power law for brightness perception. If images are not gamma-encoded, they allocate too many bits or too much bandwidth to highlights that humans cannot differentiate, and too few bits or too little bandwidth to shadow values that humans are sensitive to and would require more bits/bandwidth to maintain the same visual quality.

https://blog.amerlux.com/4-things-architects-should-know-about-lumens-vs-perceived-brightness/

cones manage color receptivity, rods determine how large our pupils should be. The larger (more dilated) our pupils are, the more light enters our eyes. In dark situations, our rods dilate our pupils so we can see better. This impacts how we perceive brightness.

https://www.cambridgeincolour.com/tutorials/gamma-correction.htm

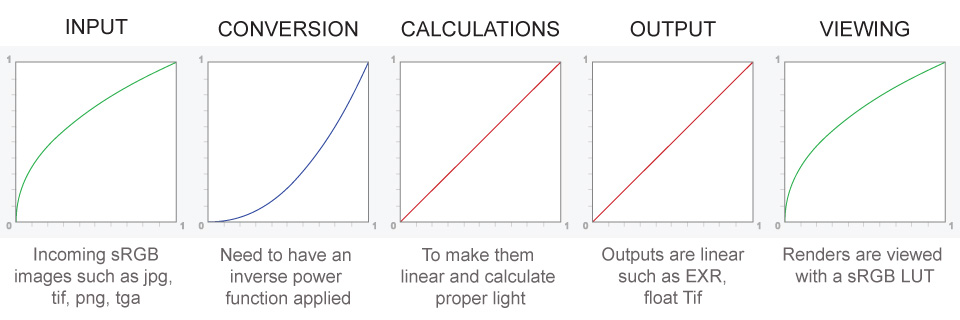

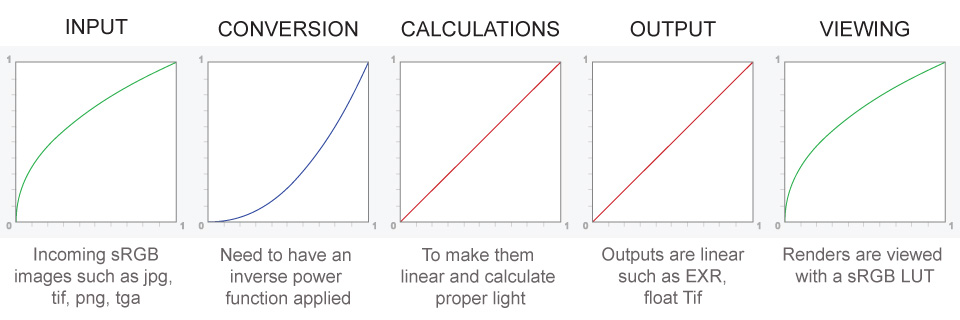

A gamma encoded image has to have “gamma correction” applied when it is viewed — which effectively converts it back into light from the original scene. In other words, the purpose of gamma encoding is for recording the image — not for displaying the image. Fortunately this second step (the “display gamma”) is automatically performed by your monitor and video card. The following diagram illustrates how all of this fits together:

Display gamma

The display gamma can be a little confusing because this term is often used interchangeably with gamma correction, since it corrects for the file gamma. This is the gamma that you are controlling when you perform monitor calibration and adjust your contrast setting. Fortunately, the industry has converged on a standard display gamma of 2.2, so one doesn’t need to worry about the pros/cons of different values.Gamma encoding of images is used to optimize the usage of bits when encoding an image, or bandwidth used to transport an image, by taking advantage of the non-linear manner in which humans perceive light and color. Human response to luminance is also biased. Especially sensible to dark areas.

Thus, the human visual system has a non-linear response to the power of the incoming light, so a fixed increase in power will not have a fixed increase in perceived brightness.

We perceive a value as half bright when it is actually 18% of the original intensity not 50%. As such, our perception is not linear.You probably already know that a pixel can have any ‘value’ of Red, Green, and Blue between 0 and 255, and you would therefore think that a pixel value of 127 would appear as half of the maximum possible brightness, and that a value of 64 would represent one-quarter brightness, and so on. Well, that’s just not the case.

Pixar Color Management

https://renderman.pixar.com/color-management

– Why do we need linear gamma?

Because light works linearly and therefore only works properly when it lights linear values.– Why do we need to view in sRGB?

Because the resulting linear image in not suitable for viewing, but contains all the proper data. Pixar’s IT viewer can compensate by showing the rendered image through a sRGB look up table (LUT), which is identical to what will be the final image after the sRGB gamma curve is applied in post.This would be simple enough if every software would play by the same rules, but they don’t. In fact, the default gamma workflow for many 3D software is incorrect. This is where the knowledge of a proper imaging workflow comes in to save the day.

Cathode-ray tubes have a peculiar relationship between the voltage applied to them, and the amount of light emitted. It isn’t linear, and in fact it follows what’s called by mathematicians and other geeks, a ‘power law’ (a number raised to a power). The numerical value of that power is what we call the gamma of the monitor or system.

Thus. Gamma describes the nonlinear relationship between the pixel levels in your computer and the luminance of your monitor (the light energy it emits) or the reflectance of your prints. The equation is,

Luminance = C * value^gamma + black level

– C is set by the monitor Contrast control.

– Value is the pixel level normalized to a maximum of 1. For an 8 bit monitor with pixel levels 0 – 255, value = (pixel level)/255.

– Black level is set by the (misnamed) monitor Brightness control. The relationship is linear if gamma = 1. The chart illustrates the relationship for gamma = 1, 1.5, 1.8 and 2.2 with C = 1 and black level = 0.

Gamma affects middle tones; it has no effect on black or white. If gamma is set too high, middle tones appear too dark. Conversely, if it’s set too low, middle tones appear too light.

The native gamma of monitors – the relationship between grid voltage and luminance – is typically around 2.5, though it can vary considerably. This is well above any of the display standards, so you must be aware of gamma and correct it.

A display gamma of 2.2 is the de facto standard for the Windows operating system and the Internet-standard sRGB color space.

The old standard for Mcintosh and prepress file interchange is 1.8. It is now 2.2 as well.

Video cameras have gammas of approximately 0.45 – the inverse of 2.2. The viewing or system gamma is the product of the gammas of all the devices in the system – the image acquisition device (film+scanner or digital camera), color lookup table (LUT), and monitor. System gamma is typically between 1.1 and 1.5. Viewing flare and other factor make images look flat at system gamma = 1.0.

Most laptop LCD screens are poorly suited for critical image editing because gamma is extremely sensitive to viewing angle.

More about screens

https://www.cambridgeincolour.com/tutorials/gamma-correction.htm

CRT Monitors. Due to an odd bit of engineering luck, the native gamma of a CRT is 2.5 — almost the inverse of our eyes. Values from a gamma-encoded file could therefore be sent straight to the screen and they would automatically be corrected and appear nearly OK. However, a small gamma correction of ~1/1.1 needs to be applied to achieve an overall display gamma of 2.2. This is usually already set by the manufacturer’s default settings, but can also be set during monitor calibration.

LCD Monitors. LCD monitors weren’t so fortunate; ensuring an overall display gamma of 2.2 often requires substantial corrections, and they are also much less consistent than CRT’s. LCDs therefore require something called a look-up table (LUT) in order to ensure that input values are depicted using the intended display gamma (amongst other things). See the tutorial on monitor calibration: look-up tables for more on this topic.

About black level (brightness). Your monitor’s brightness control (which should actually be called black level) can be adjusted using the mostly black pattern on the right side of the chart. This pattern contains two dark gray vertical bars, A and B, which increase in luminance with increasing gamma. (If you can’t see them, your black level is way low.) The left bar (A) should be just above the threshold of visibility opposite your chosen gamma (2.2 or 1.8) – it should be invisible where gamma is lower by about 0.3. The right bar (B) should be distinctly visible: brighter than (A), but still very dark. This chart is only for monitors; it doesn’t work on printed media.

The 1.8 and 2.2 gray patterns at the bottom of the image represent a test of monitor quality and calibration. If your monitor is functioning properly and calibrated to gamma = 2.2 or 1.8, the corresponding pattern will appear smooth neutral gray when viewed from a distance. Any waviness, irregularity, or color banding indicates incorrect monitor calibration or poor performance.

Another test to see whether one’s computer monitor is properly hardware adjusted and can display shadow detail in sRGB images properly, they should see the left half of the circle in the large black square very faintly but the right half should be clearly visible. If not, one can adjust their monitor’s contrast and/or brightness setting. This alters the monitor’s perceived gamma. The image is best viewed against a black background.

This procedure is not suitable for calibrating or print-proofing a monitor. It can be useful for making a monitor display sRGB images approximately correctly, on systems in which profiles are not used (for example, the Firefox browser prior to version 3.0 and many others) or in systems that assume untagged source images are in the sRGB colorspace.

On some operating systems running the X Window System, one can set the gamma correction factor (applied to the existing gamma value) by issuing the command xgamma -gamma 0.9 for setting gamma correction factor to 0.9, and xgamma for querying current value of that factor (the default is 1.0). In OS X systems, the gamma and other related screen calibrations are made through the System Preference

https://www.kinematicsoup.com/news/2016/6/15/gamma-and-linear-space-what-they-are-how-they-differ

Linear color space means that numerical intensity values correspond proportionally to their perceived intensity. This means that the colors can be added and multiplied correctly. A color space without that property is called ”non-linear”. Below is an example where an intensity value is doubled in a linear and a non-linear color space. While the corresponding numerical values in linear space are correct, in the non-linear space (gamma = 0.45, more on this later) we can’t simply double the value to get the correct intensity.

The need for gamma arises for two main reasons: The first is that screens have been built with a non-linear response to intensity. The other is that the human eye can tell the difference between darker shades better than lighter shades. This means that when images are compressed to save space, we want to have greater accuracy for dark intensities at the expense of lighter intensities. Both of these problems are resolved using gamma correction, which is to say the intensity of every pixel in an image is put through a power function. Specifically, gamma is the name given to the power applied to the image.

CRT screens, simply by how they work, apply a gamma of around 2.2, and modern LCD screens are designed to mimic that behavior. A gamma of 2.2, the reciprocal of 0.45, when applied to the brightened images will darken them, leaving the original image.

LIGHTING

-

Gamma correction

Read more: Gamma correction

http://www.normankoren.com/makingfineprints1A.html#Gammabox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamma_correction

http://www.photoscientia.co.uk/Gamma.htm

https://www.w3.org/Graphics/Color/sRGB.html

http://www.eizoglobal.com/library/basics/lcd_display_gamma/index.html

https://forum.reallusion.com/PrintTopic308094.aspx

Basically, gamma is the relationship between the brightness of a pixel as it appears on the screen, and the numerical value of that pixel. Generally Gamma is just about defining relationships.

Three main types:

– Image Gamma encoded in images

– Display Gammas encoded in hardware and/or viewing time

– System or Viewing Gamma which is the net effect of all gammas when you look back at a final image. In theory this should flatten back to 1.0 gamma.Our eyes, different camera or video recorder devices do not correctly capture luminance. (they are not linear)

Different display devices (monitor, phone screen, TV) do not display luminance correctly neither. So, one needs to correct them, therefore the gamma correction function.The human perception of brightness, under common illumination conditions (not pitch black nor blindingly bright), follows an approximate power function (note: no relation to the gamma function), with greater sensitivity to relative differences between darker tones than between lighter ones, consistent with the Stevens’ power law for brightness perception. If images are not gamma-encoded, they allocate too many bits or too much bandwidth to highlights that humans cannot differentiate, and too few bits or too little bandwidth to shadow values that humans are sensitive to and would require more bits/bandwidth to maintain the same visual quality.

https://blog.amerlux.com/4-things-architects-should-know-about-lumens-vs-perceived-brightness/

cones manage color receptivity, rods determine how large our pupils should be. The larger (more dilated) our pupils are, the more light enters our eyes. In dark situations, our rods dilate our pupils so we can see better. This impacts how we perceive brightness.

https://www.cambridgeincolour.com/tutorials/gamma-correction.htm

A gamma encoded image has to have “gamma correction” applied when it is viewed — which effectively converts it back into light from the original scene. In other words, the purpose of gamma encoding is for recording the image — not for displaying the image. Fortunately this second step (the “display gamma”) is automatically performed by your monitor and video card. The following diagram illustrates how all of this fits together:

Display gamma

The display gamma can be a little confusing because this term is often used interchangeably with gamma correction, since it corrects for the file gamma. This is the gamma that you are controlling when you perform monitor calibration and adjust your contrast setting. Fortunately, the industry has converged on a standard display gamma of 2.2, so one doesn’t need to worry about the pros/cons of different values.Gamma encoding of images is used to optimize the usage of bits when encoding an image, or bandwidth used to transport an image, by taking advantage of the non-linear manner in which humans perceive light and color. Human response to luminance is also biased. Especially sensible to dark areas.

Thus, the human visual system has a non-linear response to the power of the incoming light, so a fixed increase in power will not have a fixed increase in perceived brightness.

We perceive a value as half bright when it is actually 18% of the original intensity not 50%. As such, our perception is not linear.You probably already know that a pixel can have any ‘value’ of Red, Green, and Blue between 0 and 255, and you would therefore think that a pixel value of 127 would appear as half of the maximum possible brightness, and that a value of 64 would represent one-quarter brightness, and so on. Well, that’s just not the case.

Pixar Color Management

https://renderman.pixar.com/color-management

– Why do we need linear gamma?

Because light works linearly and therefore only works properly when it lights linear values.– Why do we need to view in sRGB?

Because the resulting linear image in not suitable for viewing, but contains all the proper data. Pixar’s IT viewer can compensate by showing the rendered image through a sRGB look up table (LUT), which is identical to what will be the final image after the sRGB gamma curve is applied in post.This would be simple enough if every software would play by the same rules, but they don’t. In fact, the default gamma workflow for many 3D software is incorrect. This is where the knowledge of a proper imaging workflow comes in to save the day.

Cathode-ray tubes have a peculiar relationship between the voltage applied to them, and the amount of light emitted. It isn’t linear, and in fact it follows what’s called by mathematicians and other geeks, a ‘power law’ (a number raised to a power). The numerical value of that power is what we call the gamma of the monitor or system.

Thus. Gamma describes the nonlinear relationship between the pixel levels in your computer and the luminance of your monitor (the light energy it emits) or the reflectance of your prints. The equation is,

Luminance = C * value^gamma + black level

– C is set by the monitor Contrast control.

– Value is the pixel level normalized to a maximum of 1. For an 8 bit monitor with pixel levels 0 – 255, value = (pixel level)/255.

– Black level is set by the (misnamed) monitor Brightness control. The relationship is linear if gamma = 1. The chart illustrates the relationship for gamma = 1, 1.5, 1.8 and 2.2 with C = 1 and black level = 0.

Gamma affects middle tones; it has no effect on black or white. If gamma is set too high, middle tones appear too dark. Conversely, if it’s set too low, middle tones appear too light.

The native gamma of monitors – the relationship between grid voltage and luminance – is typically around 2.5, though it can vary considerably. This is well above any of the display standards, so you must be aware of gamma and correct it.

A display gamma of 2.2 is the de facto standard for the Windows operating system and the Internet-standard sRGB color space.

The old standard for Mcintosh and prepress file interchange is 1.8. It is now 2.2 as well.

Video cameras have gammas of approximately 0.45 – the inverse of 2.2. The viewing or system gamma is the product of the gammas of all the devices in the system – the image acquisition device (film+scanner or digital camera), color lookup table (LUT), and monitor. System gamma is typically between 1.1 and 1.5. Viewing flare and other factor make images look flat at system gamma = 1.0.

Most laptop LCD screens are poorly suited for critical image editing because gamma is extremely sensitive to viewing angle.

More about screens

https://www.cambridgeincolour.com/tutorials/gamma-correction.htm

CRT Monitors. Due to an odd bit of engineering luck, the native gamma of a CRT is 2.5 — almost the inverse of our eyes. Values from a gamma-encoded file could therefore be sent straight to the screen and they would automatically be corrected and appear nearly OK. However, a small gamma correction of ~1/1.1 needs to be applied to achieve an overall display gamma of 2.2. This is usually already set by the manufacturer’s default settings, but can also be set during monitor calibration.

LCD Monitors. LCD monitors weren’t so fortunate; ensuring an overall display gamma of 2.2 often requires substantial corrections, and they are also much less consistent than CRT’s. LCDs therefore require something called a look-up table (LUT) in order to ensure that input values are depicted using the intended display gamma (amongst other things). See the tutorial on monitor calibration: look-up tables for more on this topic.

About black level (brightness). Your monitor’s brightness control (which should actually be called black level) can be adjusted using the mostly black pattern on the right side of the chart. This pattern contains two dark gray vertical bars, A and B, which increase in luminance with increasing gamma. (If you can’t see them, your black level is way low.) The left bar (A) should be just above the threshold of visibility opposite your chosen gamma (2.2 or 1.8) – it should be invisible where gamma is lower by about 0.3. The right bar (B) should be distinctly visible: brighter than (A), but still very dark. This chart is only for monitors; it doesn’t work on printed media.

The 1.8 and 2.2 gray patterns at the bottom of the image represent a test of monitor quality and calibration. If your monitor is functioning properly and calibrated to gamma = 2.2 or 1.8, the corresponding pattern will appear smooth neutral gray when viewed from a distance. Any waviness, irregularity, or color banding indicates incorrect monitor calibration or poor performance.

Another test to see whether one’s computer monitor is properly hardware adjusted and can display shadow detail in sRGB images properly, they should see the left half of the circle in the large black square very faintly but the right half should be clearly visible. If not, one can adjust their monitor’s contrast and/or brightness setting. This alters the monitor’s perceived gamma. The image is best viewed against a black background.

This procedure is not suitable for calibrating or print-proofing a monitor. It can be useful for making a monitor display sRGB images approximately correctly, on systems in which profiles are not used (for example, the Firefox browser prior to version 3.0 and many others) or in systems that assume untagged source images are in the sRGB colorspace.

On some operating systems running the X Window System, one can set the gamma correction factor (applied to the existing gamma value) by issuing the command xgamma -gamma 0.9 for setting gamma correction factor to 0.9, and xgamma for querying current value of that factor (the default is 1.0). In OS X systems, the gamma and other related screen calibrations are made through the System Preference

https://www.kinematicsoup.com/news/2016/6/15/gamma-and-linear-space-what-they-are-how-they-differ

Linear color space means that numerical intensity values correspond proportionally to their perceived intensity. This means that the colors can be added and multiplied correctly. A color space without that property is called ”non-linear”. Below is an example where an intensity value is doubled in a linear and a non-linear color space. While the corresponding numerical values in linear space are correct, in the non-linear space (gamma = 0.45, more on this later) we can’t simply double the value to get the correct intensity.

The need for gamma arises for two main reasons: The first is that screens have been built with a non-linear response to intensity. The other is that the human eye can tell the difference between darker shades better than lighter shades. This means that when images are compressed to save space, we want to have greater accuracy for dark intensities at the expense of lighter intensities. Both of these problems are resolved using gamma correction, which is to say the intensity of every pixel in an image is put through a power function. Specifically, gamma is the name given to the power applied to the image.

CRT screens, simply by how they work, apply a gamma of around 2.2, and modern LCD screens are designed to mimic that behavior. A gamma of 2.2, the reciprocal of 0.45, when applied to the brightened images will darken them, leaving the original image.

-

Simulon – a Hollywood production studio app in the hands of an independent creator with access to consumer hardware, LDRi to HDRi through ML

Read more: Simulon – a Hollywood production studio app in the hands of an independent creator with access to consumer hardware, LDRi to HDRi through MLDivesh Naidoo: The video below was made with a live in-camera preview and auto-exposure matching, no camera solve, no HDRI capture and no manual compositing setup. Using the new Simulon phone app.

LDR to HDR through ML

https://simulon.typeform.com/betatest

Process example

-

LUX vs LUMEN vs NITS vs CANDELA – What is the difference

Read more: LUX vs LUMEN vs NITS vs CANDELA – What is the differenceMore details here: Lumens vs Candelas (candle) vs Lux vs FootCandle vs Watts vs Irradiance vs Illuminance

https://www.inhouseav.com.au/blog/beginners-guide-nits-lumens-brightness/

Candela

Candela is the basic unit of measure of the entire volume of light intensity from any point in a single direction from a light source. Note the detail: it measures the total volume of light within a certain beam angle and direction.

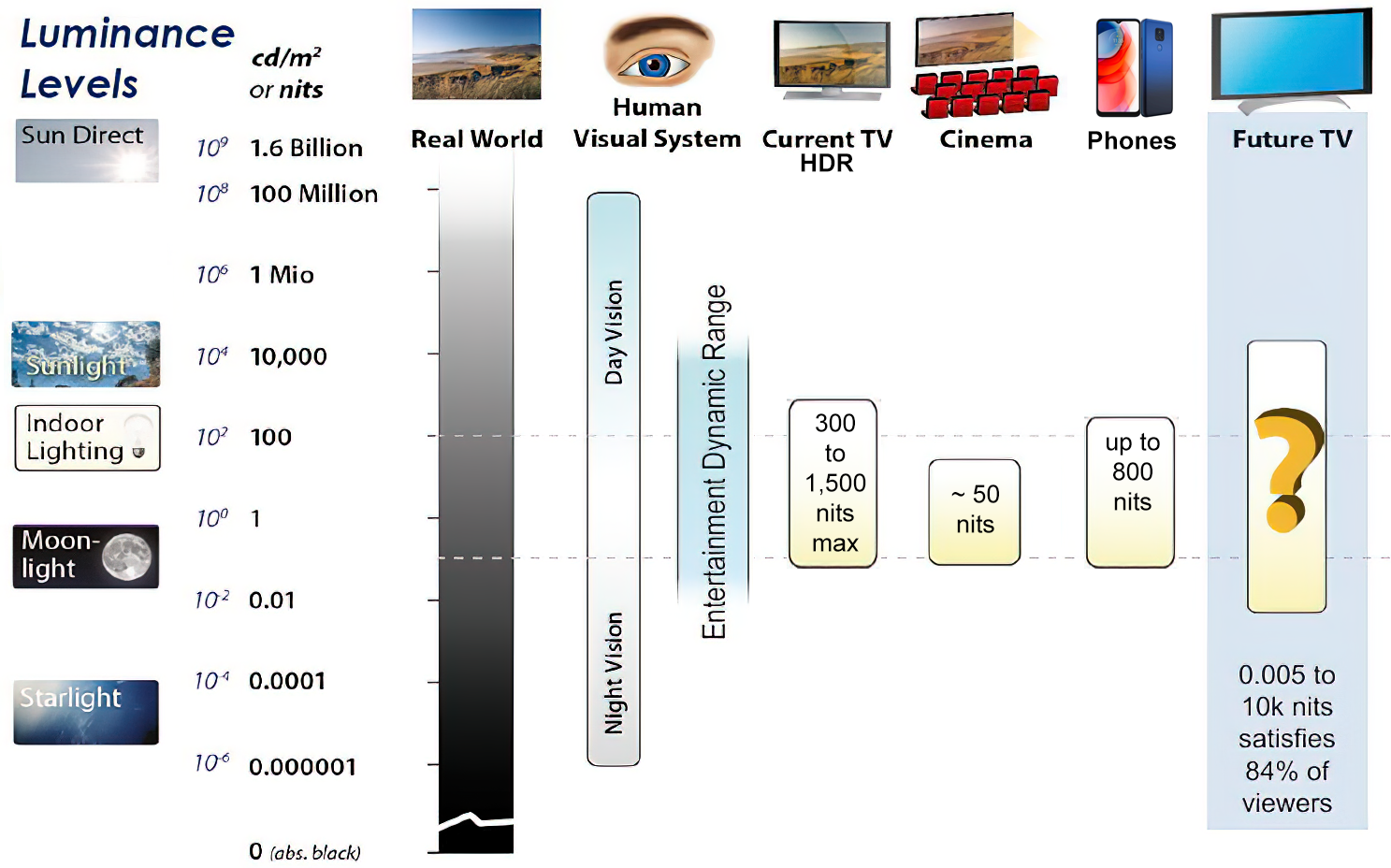

While the luminance of starlight is around 0.001 cd/m2, that of a sunlit scene is around 100,000 cd/m2, which is a hundred millions times higher. The luminance of the sun itself is approximately 1,000,000,000 cd/m2.NIT

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candela_per_square_metre

The candela per square metre (symbol: cd/m2) is the unit of luminance in the International System of Units (SI). The unit is based on the candela, the SI unit of luminous intensity, and the square metre, the SI unit of area. The nit (symbol: nt) is a non-SI name also used for this unit (1 nt = 1 cd/m2).[1] The term nit is believed to come from the Latin word nitēre, “to shine”. As a measure of light emitted per unit area, this unit is frequently used to specify the brightness of a display device.

NIT and cd/m2 (candela power) represent the same thing and can be used interchangeably. One nit is equivalent to one candela per square meter, where the candela is the amount of light which has been emitted by a common tallow candle, but NIT is not part of the International System of Units (abbreviated SI, from Systeme International, in French).

It’s easiest to think of a TV as emitting light directly, in much the same way as the Sun does. Nits are simply the measurement of the level of light (luminance) in a given area which the emitting source sends to your eyes or a camera sensor.

The Nit can be considered a unit of visible-light intensity which is often used to specify the brightness level of an LCD.

1 Nit is approximately equal to 3.426 Lumens. To work out a comparable number of Nits to Lumens, you need to multiply the number of Nits by 3.426. If you know the number of Lumens, and wish to know the Nits, simply divide the number of Lumens by 3.426.

Most consumer desktop LCDs have Nits of 200 to 300, the average TV most likely has an output capability of between 100 and 200 Nits, and an HDR TV ranges from 400 to 1,500 Nits.

Virtual Production sets currently sport around 6000 NIT ceiling and 1000 NIT wall panels.The ambient brightness of a sunny day with clear blue skies is between 7000-10,000 nits (between 3000-7000 nits for overcast skies and indirect sunlight).

A bright sunny day can have specular highlights that reach over 100,000 nits. Direct sunlight is around 1,600,000,000 nits.

10,000 nits is also the typical brightness of a fluorescent tube – bright, but not painful to look at.

https://www.displaydaily.com/article/display-daily/dolby-vision-vs-hdr10-clarified

Tests showed that a “black level” of 0.005 nits (cd/m²) satisfied the vast majority of viewers. While 0.005 nits is very close to true black, Griffis says Dolby can go down to a black of 0.0001 nits, even though there is no need or ability for displays to get that dark today.

How bright is white? Dolby says the range of 0.005 nits – 10,000 nits satisfied 84% of the viewers in their viewing tests.

The brightest consumer HDR displays today are about 1,500 nits. Professional displays where HDR content is color-graded can achieve up to 4,000 nits peak brightness.High brightness that would be in danger of damaging the eye would be in the neighborhood of 250,000 nits.

Lumens

Lumen is a measure of how much light is emitted (luminance, luminous flux) by an object. It indicates the total potential amount of light from a light source that is visible to the human eye.

Lumen is commonly used in the context of light bulbs or video-projectors as a metric for their brightness power.Lumen is used to describe light output, and about video projectors, it is commonly referred to as ANSI Lumens. Simply put, lumens is how to find out how bright a LED display is. The higher the lumens, the brighter to display!

Technically speaking, a Lumen is the SI unit of luminous flux, which is equal to the amount of light which is emitted per second in a unit solid angle of one steradian from a uniform source of one-candela intensity radiating in all directions.

LUX

Lux (lx) or often Illuminance, is a photometric unit along a given area, which takes in account the sensitivity of human eye to different wavelenghts. It is the measure of light at a specific distance within a specific area at that distance. Often used to measure the incidental sun’s intensity.

Collections

| Explore posts

| Design And Composition

| Featured AI

Popular Searches

unreal | pipeline | virtual production | free | learn | photoshop | 360 | macro | google | nvidia | resolution | open source | hdri | real-time | photography basics | nuke

FEATURED POSTS

Social Links

DISCLAIMER – Links and images on this website may be protected by the respective owners’ copyright. All data submitted by users through this site shall be treated as freely available to share.